This week’s post is written by David M. Sanders, AIA a residential architect based in Capistrano Beach, California. David has generously shared his own system for preparing the ultimate set of construction documents.

You may learn more about David and his firm at his website. Send him an email and say thanks for sharing such valuable information.

Many of us here at Entrepreneur Architect have taken the excellent advice of our host and begun to strengthen our marketing plans. For myself, it has indeed made a notable difference and I have to thank Mark for the valuable insights he has shared.

Getting more conversions is great, and important, but what about the other end of the equation? We’re all fairly adept at providing good design for our clients and successfully presenting to them. Most of us do that effectively by various means, whether it be Richardsonian esquisse, Wrightian colored pencil renderings, or crisp photo-real renderings of our computer models. After that, we move into production, and this is where I see a lot of practitioners burn up time (and thus money) by reinventing the wheel on every project. I’d like to share my methods with the group in the interest of making us all stronger in a critical skill; Construction Document production.

Since my early years in the profession, I’ve always had a bit of OCD about organization and have been quickly put in charge of the drafting standard at firms I’ve worked at. After three decades, I feel like I’ve arrived at an ideal system, which is an adapted compilation of two known standards: The AIA’s ‘ConDoc’ system and the ‘NCS’ (National Cad Standard).

ConDoc was invented several years ago and is a familiar system to commercial practitioners. There’s a handy two-page synopsis available at this link: http://www.aia.org/aiaucmp/groups/secure/documents/pdf/aiap016662.pdf.

The NCS is a more comprehensive scheme that gets into the real nitty-gritty of the documentation process and is commonly utilized for governmental projects. You can view its several modules at this link: http://www.nationalcadstandard.org/ncs5/content.php. Both links are worth a look to gain an understanding of the respective philosophies.

The trick was to figure out a simplified system for use on projects of residential scale that is flexible enough to adapt to anything from a room addition to a large, luxury home. Following are the techniques I’ve settled on that have given me maximum ‘bang for the minute’ of drafting time.

Step 1: Your Master Specification

The first step is to develop a solid, categorized master specification. Mine is assembled in a Word document, and is laid out as a narrow column that fits a half-width of my standard NCS sheet module. It’s categorized in the simple six-digit CSI (Construction Specification Institute) format. You can download CSI’s MasterFormat list at this link: http://www.csinet.org/numbersandtitles. Some sections utilize an additional two-digit modifier at the end of the six-digit number, which I typically modify by simply changing the third number set to the next in sequence from the one above it; that way, all the section numbers are simply six digits, and fit better on the drawing sheets. I make a copy of this master specification for each project, and place it in the project’s folder. While working on the CD’s, I have the specification file open so that I can quickly refer to its table of contents while generating annotation on the drawing sheets, and I’m also editing it to suit the project at hand. If you prefer to use the OmniClass system of specification categorization, it works just as well. I’m an old man, and have the six-digit MasterFormat system practically memorized, so I’ve stuck with it.

Step 2: Your Drawing Index

Step two is to setup the drawing index in the CSI Uniform Drawing System (UDS). Sheets are assigned alphanumeric numbers based on construction discipline and sheet order. This methodology is incredibly handy when you need to add or subtract sheets from your drawing sets, as doing so doesn’t screw up any sheet references embedded in the drawings, such as section and detail sheet references.

Step 3: Your Keynote System

The third step is to devise a consistent keynoting system. On large-format drawings, always use keynotes; no exceptions. If I catch someone making verbal annotations on a plan, elevation or section, they’ll quickly get a scale across the knuckles. It’s vitally important to be consistent in your annotation technique. The only place ‘contextual’ notes are used is in detail drawings (where keynotes are not as effective for the contractors).

Step 4: Scheduling

Fourth is scheduling. Doors, windows, room finish, equipment, plumbing fixtures, appliances, electrical devices and lighting are always scheduled. This does two things: It allows you to fully specify components to any degree you wish, and it creates a quick-to-reference list for any participant in the project. When you need to obtain quotes for these scheduled items, you can simply send a link to the drawing set to your suppliers, and direct them to the sheet where the schedule they need to see is located. This insures complete, concise quotations from the suppliers. If substitutions are made, it happens in one place and is easy to point to for other project participants. Also, you can integrate door and window detail references into your schedules which reduces clutter on your elevation and section drawings. Some folks don’t think this is effective and is easily missed, but if you explain your system to the contractors, you’ll find they will quickly embrace it.

Here’s how it all comes together…

First, I place a box on the Title Sheet of the drawings that illustrates my drafting symbols for the set. I point it out to the contractors at the pre-bid meeting to be sure they’re aware of it. It looks like this:

Notice that the keynote marker description clearly states that the keynotes listed on any particular page apply to that page only. That way, you don’t have to try to track note numbers through the entire set. That’s a departure from the ConDoc / NCS standard, which tries to use the six-digit CSI numbers as keynote numbers (which are very cumbersome to read).

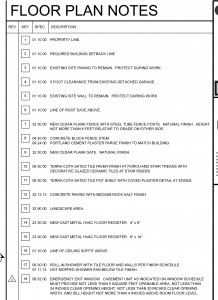

Next are the typically large format drawing sheets. With the exception of detail or wall section sheets, each drawing sheet has a column of keynotes on its right-hand edge composed of four sub-columns: A column for revision deltas, a column for the keynote symbol, a column for the specification section reference, and a column for the note description. Like this:

Notice that the descriptions are typically very short, and only say what needs to be said for cognition of what is being called out. The only time they get ‘wordy’ is if the AHJ wants you to expand on something; as in the case with note number 18 on this set. The idea is that we want the drawings to be quick to read in the field. If the person looking at the drawings needs more information, they can look in the listed specification section where there’s a plethora of information for them to digest. In most cases, they only need to see that extensive amount of information one time, so we want it in one place.

This is extremely valuable for two reasons: If it needs to be edited, it is done in one place without any need to try to find instances throughout the set, and; it leaves lots of space to add notes on the drawing sheet so you can annotate your drawings more thoroughly. Another great benefit is that you can often reuse a large number of notes on other projects by simply copying and pasting to build up note lists for new projects. If you can stay disciplined and stick with your system, it can be a huge time-saver. Also notice that a single keynote can reference as many specification sections as you like, such as note number 17 which calls out the tile finish at the shower as well as the shower pan waterproofing. That note also references the finish schedule. Lets take a look at the note column there:

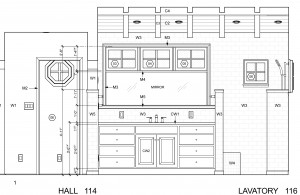

It’s slightly different than the normal keynote list. The key numbers are not boxed, so that they can be inserted in the Room Finish Schedule as normal text. Also, this same column of notes is placed on the interior elevation sheets, and the key numbers are used to call out items on the elevations like this:

You can see how clean this leaves the drawing, making it much more comprehensible and with plenty of room for dimensions. This has the same benefit as the normal keynotes; You can change a material or finish specification without having to ‘chase’ it through the drawing set.

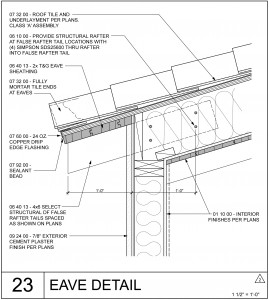

Finally, there’s the detail drawings. Even though they don’t get keynotes, they do get specification references. They look like this:

The specification section leads the notation with a hyphen between, which creates a clear separation between the specification reference and the description of the component. Also, I tend to kick as many detailed notes back to the large format drawings, which minimizes duplication of data and makes it easier to perform subtle edits. For instance, in this detail, I don’t need to tell the contractor the precise texture and color of the exterior cement plaster finish; that’s on the exterior elevations. All (s)he needs to know for the purpose of this drawing is that it’s a 7/8 inch thick layer of the stuff… (S)he already saw it’s color and texture called out on the elevations. Another side note on details; I like to give each detail an individual number, no matter what sheet it occurs on. By never duplicating a detail number, you’ll have no confusion even if there’s an error in the detail bubble’s sheet reference. It also makes it easier to write each detail to a computer file without having to track it’s location in the drawing set (i.e., 001.dwg, 002.dwg,….. 099.dwg, 100.dwg, etc.)

Once the drawings are complete, the edited and culled specifications are placed on a drawing sheet for inclusion in the set. This can be done by Object Linking and Embedding (OLE) in some software packages, which will make the placed text track changes in the source file, or you can simply copy and paste them section by section.

Personally, I use ArchiCAD software (which I highly recommend). It’s a full-featured BIM package with two discrete components; a modeling section and a layout section. You can use it several ways, but my personal method is to try to do as little annotation as possible in the modeling section. All my keynotes are placed in the layout section. The exceptions to this are the material / finish callouts on the interior elevations and detail / section markers which I find easier to keep track of in the modeling section. Additionally, the door, window and room markers are generated within the modeling section where they serve as the database to feed my schedules. If you’re using 2D drafting software, you won’t be able to harness such automation, but that’s a separate topic. Let me know if y’all would like a full dissertation on my BIM philosophy (it’s an earful!).

The main ideas to improve accuracy and speed up your production processes are as follows:

- Do your detailed specifications in ONE place, not scattered around the drawing set.

- Always have every note refer back to the applicable specification section(s). Even very generalized notes, such as ‘Roof eave above’ refer back to specification section 01 10 00, which has extensive notes directing the contractor to pay attention to alignments, proper fit of components, etc.

- Make a clear distinction between graphic content and verbal content.

- Pick a method for each particular task, one that is simple and versatile, and then stick to it! Don’t cheat.

- Analyze your software packages’ capabilities and automate as many functions as you can by utilizing database generated schedules, automated drawing titles and master layouts for drawing sheets. Know your tool kit.

Once you habituate to a solid system, you’ll see your productivity soar, and you’ll realize a more satisfying net hourly on that lump sum fee! 😉 Or, even better, use that time gained to dazzle your client with your generous amount of time allotted for site visits and your cheerful, relaxed response to RFI’s.

One of the highest compliments I can get is a contractor telling me, “This is an awesome set of drawings.” I get that quite a lot, and am quite proud of it. The best part, though, and the part I keep more private, is that it’s much quicker to produce these drawings! I hope some these ideas and concepts can help to increase your productivity, provide your clients with tighter bids, and give you more control over the built conditions on your projects.

Let me know what you think of my system. Do you have any more tips to streamline our productivity? Share your ideas in the comments below.

I really appreciate and relate to this post David. The first architect I ever worked would pass on compliments from contractors that were building from our drawings which were organized in a similar fashion and it really does hit home to hear good stuff from the builders.

My questions:

What do you say to the critics that call these standards “overkill” or a “practice that runs up fee”? Is this level of detail and documentation due to being in a high tier custom market?

Also, do you take or have you done commercial projects? It seems your system would easily lend itself to that work.

Thanks again for the post. Big Time Small Firms UNITE!

~Jes

Jes,

“What do you say to the critics that call these standards “overkill” or a “practice that runs up fee”?”

I tell them that a more complete, tightly specified drawing set yields a tighter construction bid and minimizes charges for extras and change orders. The contractor signs a contract to provide Work ‘in accordance with the construction documents’. If we do a nice, tight set then our clients will get a true picture of the cost at the beginning of the project, which they always appreciate in the end. Responsible contractors like this, too; It minimizes the unpleasant need to hit the client with extras, which are always unwelcome, no matter how good natured the client may be. I consider complete, well specified CD’s to be a significant part of providing responsible service to my clients, and explain that to them early in the process. The well spec’d CD’s can be a valuable tool in the value engineering phase of the project, too.

“Also, do you take or have you done commercial projects? It seems your system would easily lend itself to that work.”

I don’t take on much commercial work of my own, but do consult on commercial projects frequently. This system works just as well for those jobs.

Thanks for giving it a read!

David,

Nice drawing system and I fully agree with your response to critics. I’ve implemented a very similar system to yours in our office which is based on a similar system from my previous employer. We completed complex hospital projects north of $100M with a cad standards system nearly identical to what you are using so, I’d say it’s perfectly suited to commercial, institutional and residential work. I find it so nice to a have a clear, rigorous system in place to pass instruction onto drafts-persons, coordinate with consultants, and for ease of work with contractors. Plus it saves my sanity and speeds the production process along.

David-

Great blog post! I truly appreciate the system that you have created as I try to do the same things. I learned this by working in some large corporate firms that have systems in place to make the production, coordination and consistency work in your favor rather than a nightmare that can occur if not watched.

I too use ArchiCAD (12 years) and it definitely makes this process so much more clear and the drawings look fantastic! Especially 3D details!

Chad Conrad

Great system and thanks for sharing in so much detail. This kind of productivity and accuracy of cross referencing is one of the big advantages of BIM software. And you can have a standard office keynote file to use or customise per project.

Takes all types to fill the freeways. Maybe I am in the minority, but I have never liked the keynote system. Architecture being a subjective profession, we all have our preferences. So I don’t think one way is necessarily is right or another way wrong. I have my reasons for not liking it as I am sure David has his for loving it. Maybe a topic for discussion on a future BTSF hangout?

Systems and standards would be a great topic, Tim.

What a fantastic strategy that you’ve assembled. It would great to see how such a system could be scaled up to larger projects.

Good post and lots of great info. Very similar to my way of doing dwgs. However, I don’t get into that detail with regards to CSI specs, occasionally I’ll do book specs if the project warrants. Seems to be creating another possible coordination issue tying a spec reference to a note. Has it been an issue?

Over the years I’ve developed a 24×36 sheet that contains all my typical specs for a residential project, has worked well with very little issue. I have the master sheet and than review/edit per each project.

Keith,

“Seems to be creating another possible coordination issue tying a spec reference to a note. Has it been an issue?”

Hasn’t been a problem. The key is to keep the drawing text as pithy as possible, then use more expansive text in the specification itself. My specs aren’t ‘over-the-top’… They’re still essentially performance specs. Some sections have proprietary items mixed in, but only a few. The beauty of creating a fresh spec (based on the template) for each project is that you can tailor it to suit the particular project. What you’re doing probably doesn’t differ a whole lot from what I’m doing.

One thing I should have mentioned and didn’t: By having my specification template open on my screen during the production process, it provides a sort of ‘checklist’ for my drawing sheet annotation. I’m always sure I’ve included all the relevant notes just by visually scanning my spec files’ table of contents and noticing what’s relevant in the drawings. I like to highlight the section numbers in the table of contents as I use the section numbers in the keynotes, which allows me to track which have been used, and which will require subsequent attention when I move to finalizing the specs before placing them in the drawing set.

My specs aren’t 3-part. Rather, they’ve been highly streamlined. There’s a format on the web called ‘Sheetspec’ which a spec writing service offices free for download (Google it, you’ll find it). My specs match their scheme fairly well. Each section still follows the order of three-part specs, but just not as broken out. I’ll list standards first, then products, then installation requirements.

dissent.

I have to say I advocate going the other way on much of this. To build a useful system is somewhat complex, but should not wear that complexity – in fact it should conceal it and make your drawings simpler for the user rather than more complicated.

Never use schedules on residential work. Schedules cause temporal displacement – a term from Edward Tufte. When you are looking at a plan and want to know something, its best if the info is there – not a symbol that refers you to elsewhere in the drawing set. Giant waste of time for the builder, and makes drawings feel dense and unfriendly.

So – door type material size – on the door on the plan. No door numbers.

Window type material operation size – on the window on the elev.

Finish information floors walls clg & hght – on the floor plan.

For example the few doors that require detailed description are then just elaborated on in the material list. My experience is Builders hate schedules. Builders hate reference marks. We take them for granted. These guys take classes on how to read blueprints. Something is wrong there.

Drawings cluttered with useful information are better than sparse drawings that make designers happy.

Res Check style material codes are simply replaced by carefully precise plain language. If you can come up with a unique number for each material, you can come up with a unique name for each material, and its so much less intimidating, and again avoids symbols and references which cause temporal displacement. No translating.

And none of this inhibits system building for your documents, in fact it makes it simpler.

Systems building is partly about making it easier and faster to create your documents. But the overall mission is to make it easier and more transparent for the people who use your drawings to read them and take away what they need. Systems should not compromise that mission by appending the stuff that makes the designers job easier, and the builders job more confusing.

Folks,

I added replies to some of the queries above, as sub-replies to the specific messages. Subsequently, I’ve not been able to see them in my browser. Hopefully, the folks I replied to can see them. Jes and Keith, were you able to see my responses?

David, your earlier comments needed authorization since this was the first time you commented at the blog. You should be good to go from now on. Thanks for the thorough replies.

Awesome post David, I saw your website and I think it is great you are sharing so much. One of the main problems I find is that when people transition to a BIM platform they don’t have a good template, and this kills their production. They also, understandably, try to us to much CAD thinking rather than BIM thinking in there modeling.

“They also, understandably, try to us to much CAD thinking rather than BIM thinking in there modeling.”

YES. I’ve done quite a bit of training aimed at this exact conundrum. I’m thinking of writing another piece that looks at this exact topic. I see a lot of folks who don’t take full advantage of a BIM workflow, and it does indeed hamper their productivity. I’ll see what I can put together on that and share with the group… Might be helpful.

Tim B and Lavar,

No argument from me; if your methods are working for you, then by all means stick with them. I’m just showing an example of a method that’s been effective for my own projects and the contractors I work with. Truth be told, one Architect I worked for in my youth had a policy of fully contextual notes, so I’ve indeed done it that way. He was a great draftsman and his plans were well specified, good looking, and effective. However, they were very crowded and ‘dense’. They were also quite difficult to track changes on and in some areas the notation would really crowd out the graphic content… particularly after plan check.

One fellow I frequently do production for has a tendency to design in a very ‘cellular’ way; there’s lots of tiny rooms, vestibules, and little transitional spaces. There may be two or three doors or wall openings in a distance of eight feet or so. For his designs, it’d be just about impossible to specify the openings to the degree he requires (very detailed) without using incredibly tiny text, or having it almost black out the drawing.

If your design style is very open and spare, then contextual notes can still work fine. Wasn’t my intention to posit this as the only way, but rather, an alternative method. The overarching message is consistency, which I think we’d all agree on. If you set out a method, it’s crucial to be sure everyone in the office is on board with it, and uses it as intended. That way, the time required to produce CD’s stays predictable and doesn’t chip away at our fees.

However you do it, one thing my mentor told me years ago has tested true: “Good drawings get respect”.

Warmest wishes on your continued success!

David, I think if you are using your line weights and graphic elements well, and using typography to your advantage, you won’t overwhelm a plan with notes. We often neglect color because we come from a history of mono-chrome reproduction, but today there is little excuse to not use color in those details. Color adds another layer of communication – communication that is direct, wordless, and takes up no space.

Mark – I have another proposal for you. Organize an online Pecha Kucha for construction documents. Get a handful of architects with differing styles of document prep, and give them 20 slides/20 seconds/slide (that is actually the Ignite format). That would be a fun and interesting way to expose a lot of different techniques.

I’m probably more in the Lavardera camp with my drawings which comes from my years as a builder. I was normally doing drawings for myself to build from and I much preferred everything right there where I needed it when I was bending over the drawing set strapped to a piece of plywood. The fewer the sheets the better and the fewer references to other sheets the better. I have found that separate specs are normally ignored by builders despite my best efforts. And I print in color for most of my jobs which the builders LOVE. Nowadays, we use .pdf’s a lot more in the field rather than paper so there’s really no excuse to go with color. My biggest and most complicated jobs are usually still under 15 sheets and I usually only need a 1/2 doz sets. I rarely specify lighting and kitchen/bathroom finishes – my typical client doesn’t want that but I do interior elevations with “suggestions”.

The flip side to this is that I’m a lot less employable in another firm as I’m so far “out of it” with regards to specification writing and CAD standards.

I appreciate this post and hope you indeed decide to do a “full dissertation on my BIM philosophy” as you suggested in your article above.

De Etta,

Okay . I’m working on it. Could be a while, though… Big topic, and it needs to be tightly focused. Figuring that out presently.

BIM has thrown our office into a bit of turmoil. The question now is what of our old 2d systems can we retain. The reality of this is very little. It has led us to question and reinvent our whole office process…good for the business long term but an expensive process in the shorterm.

Your article helps make sense of it all…now just to convince some of the older team members!

Mike; My advice is to join the Entrepreneur Architect Linkedin Group and post a question regarding this issue. I expect that you will receive a plethora of value guidance. EntreArchitect.com/Linkedin

Mike,

You’ll be able to continue using a lot of your standard 2D regulatory details; such as handrails, guards, water heater restraints, island vents, etc. The main thing that will change initially will be how you handle plan / elevation / section views; those will be ‘model derived’. As you start gaining experience with the software and integrating it into your office logistics, you’ll begin to start integrating more of the detailing with the actual building model. Your implementation and integration will change with time (mine is still evolving after 10 years!). Start off by hybridizing your new BIM methods with your old CAD methods on an initial project. See how that one goes, then on the next project see what you think it would be possible to ‘do by BIM’ on the new project that you didn’t on the previous one. Evaluate each new project as you go forward with an eye to increasing the use of BIM techniques. After a couple of years, you’ll look back and be amazed at how far you’ve come. You may also notice quicker production times and a reduction in RFI’s over the life of the projects. It can be implemented in controlled steps.

As Mark noted… Some of the folks at the LinkedIn group will also be able to give good advice on initial integration.

Wow! Great thoughts throughout here.

@ Lavardera, I’ve been in the construction industry since before 1970, done the college route for Construction Management and Business Administration degrees, been a licensed contractor since 1984, and worked for several other contractors (in California and in British Columbia), as well as been a consultant to several (both general- and sub-contractors) for a period of years in that same time. I also worked for an architectural firm for 4 of those years in the 1980s. My construction experience has been in all forms and types of commercial work and all forms of residential work. I used to write specifications manuals for the architectural firm I worked for, as well as creating all of the schedules for doors, windows, hardware, finishes, etcetera. I learned the AIA’s ConDoc system in the early 1980’s.

I’ve never heard a single complaint about systems like the AIAs ConDoc — nor any other well-organized presentation of information — from the contractors (as you mention) . . . once they actually start to use and understand these systems work. That learning experience for a contractor is about a 10-minute discussion. Most of the people I have worked with prefer this to various notes peppered throughout the drawing sheets.

As David aptly noted in the article . . . the level of clarity of the information communicated is amazing. And, the ease of updating that information with the inevitable changes through the course of design and construction is just as much so.

I’m not sure why you find issue with this. From my experience of designing and drawing (with and without using these systems) many dozens of the remodels and some of the new builds that we have constructed over the years, I would think it makes your job much easier. I wonder if you’re working with particularly fussy contractors. I would hope you’re not just resistant to change, when it can be of such benefit.

A couple more notes here:

The keynotes on the sheet should only refer to items on the same drawing sheet;

This level of organization keeps the mis-information to a minimum by minimizing the number of times the information is presented. I can’t count how many times we’ve found different information on documents from design professionals that was contradictory. I’m looking at a set right now. (Having said that, we exclude from our contracts with owners compliance with all weasel and other clauses in drawings that release design professionals from their responsibility to get the information correct. But, we also almost always work with the design professionals in the design and drawing process to alleviate this situation, and we’re very careful to pay close attention before such becomes a problem that can’t be easily solved. We all make mistakes, but we do need to respect each other and to work as effective teams on behalf of the owners that we work for.)

If the same text is repeated a number of times on the sheet, and it requires a change, that can be done in one place instead of combing over the sheets to find every instance. The one complication is when a keynote marker on the plan needs to change in only one location and not all where it was used. But that’s also a quick edit.

One thing I’m not sure of: are any of the Big-guy CAD programs (AutoCAD) now capable of searching documents for all instances of a particular word or note – thus making it easy to edit repeating notes quickly?

Just some thoughts here from a “User.” 🙂

Thanks for the thoughtful comment Robert. To follow up on your last question, AutoCAD does let you search for a specific word.

Thanks for reading and contributing your knowledge here.