After graduating, a lot of young people encounter a slow start beginning their careers in architecture. The truth is that advancement through the profession, even in later stages, is slower than in many other fields. This post, written from the perspective of an early-stage architect, tries to explain why this issue exists and how it can be overcome.

Perhaps somewhat expectedly, the text leans toward niche specialization and focusing on the specific areas where one can be strong and contribute to the whole process quickly.

Sacrifice and Patience

After getting into architecture school, one of the first things you learn is that the profession requires a lot of sacrifices and many years in order to reach success. Most architects’ careers are the most productive when they are in their 50s and 60s, which means that most architects work for decades before reaching their peak.

To support this claim, the average age of the Pritzker prize winner (as of 2021) is 64 years old. It can be very discouraging for people just starting out in the profession to wait 40 years to be recognized for their work. If architecture is a combination of design and engineering, then it is not clear why some other engineering and design professions have faster advancement.

For example, in the IT industry, which is highly profitable and ever-changing, people usually reach their peak before their 40s. Also, civil and mechanical engineers do not have to wait so long to be strong contributors in their field and highly compensated for their work. Similarly, designers in other areas have significant impacts at the beginning of their careers as well. Fashion, graphic design, and web design all allow for less experienced professionals to be more innovative.

Thus, we are driven to ask: Why is architecture different? And how can young people make a greater impact and speed up their careers?

Consequences of Mistakes

There are a couple of reasons for low levels of trust in young professionals in architecture and construction and all of them are related to the possibility of things not going as planned. It is well known that doing things the first time brings increased risks and the possibility of errors. Importantly, the cost of any errors or mistakes in AEC industries significantly exceed most other fields. This is primarily because our industries have a greater impact on the safety and health of the end users. A malfunctioning website or app will not endanger anybody’s health. The same applies to fashion, writing, graphic design, music, film, and many other professions.

Mistakes can be much more costly in our field and this is why there are more regulations and why experience is so valued. As a consequence, investors prefer to mitigate their risk, reducing the possibility of a negative outcome. It leads to clients having significantly more trust in architects who have already designed and built many successful projects, demonstrating that they have extensive experience. If they have already taken on many projects from the beginning to the end, they can do it again.

In contrast, someone taking on too much responsibility in the early stages of their career may encounter issues that they are not able to solve. And any mistakes or errors they make can have significant consequences.

Importance of Experience

This leads to the importance of experience in architecture. Is there a way to speed up the process of obtaining it or bypass the necessity of previous work on numerous projects?

Since my research work focuses on the use of algorithms in architecture, I am familiar with ways to transfer human knowledge to software. This includes having a better understanding of how people make decisions and obtain knowledge.

The system for explaining this process is called the DIKW pyramid. The acronym stands for “Data, Information, Knowledge, and Wisdom.” The first level is all of the available raw data. In today’s age, much of it is open-access and easily obtainable; however, it is unstructured and unorganized.

That is where the second level takes over: not all of the data is useful in the given context. In order to be useful, it needs to be filtered. Valuable data that serves a purpose is used as information, which is more structured than data, thus supporting the decision-making process.

Furthermore, structuring and connecting information creates knowledge through a system of procedures that use the information to reach a goal. This level depends on experience because, regardless of the information’s significance, understanding it requires a person who can correctly evaluate it.

The final level, wisdom, occurs when multiple knowledge structures are developed and deepened. It is the ability to make correct educated guesses, without repeating the whole process from the beginning. Usually based on extensive experience, wisdom allows people to make the right decisions even without consciously examining all of the aspects.

This is exactly what differentiates great architects from the rest: understanding, at the early stages, all of the potential issues that may arise in the process of work and solving them with a single approach.

Wisdom

Use of “wisdom” in architecture can be identified in very skilled and experienced architects. Without strictly naming all of the requirements of the project, they nevertheless have them all under control “by feel.”

My internship during university brought this to my attention. During studies, students are mostly taught separately about spatial organization, the basics of structural design, and, perhaps, energy efficiency. However, successful architects handle all of these requirements simultaneously. They can sketch and verbally explain functions and relations between spaces while already subconsciously incorporating structure into the design.

Later, from this design, it is quite easy to obtain solutions for the structure and make connections with the context. While a student like me needs multiple iterations to bring everything to work together, professionals with years of experience can do it in one pass.

Understanding this to be a basic fact of the profession, I wondered if there was a way to shorten the period of time that it takes to obtain “architectural wisdom.” As Malcolm Gladwell said, “It takes ten thousand hours to truly master anything. Time spent leads to experience; experience leads to proficiency; and the more proficient you are the more valuable you’ll be.”

Is this really true, and what counts toward those 10,000 hours? Can it include time spent at university and in the years right after?

Based on my number-crunching, 10,000 hours of work in architecture is reached in 1,250 days (considering 8h of work daily), which is about 5 years into one’s career (for most people). As already emphasized, that many years into an architecture career are not enough to obtain excellence in our profession. Perhaps this is because a lot of time in our career is spent handling unusable data and not valuable information. For instance, the majority of entry-level work in architecture includes largely non-design-related activities. Therefore, reaching 10,000 hours of design decisions takes a much longer period of time

Technology can help

From my personal experience, an important trick in overcoming this was getting control over the technologies for the production of projects: modeling possibilities, simulations, real-time rendering, etc.

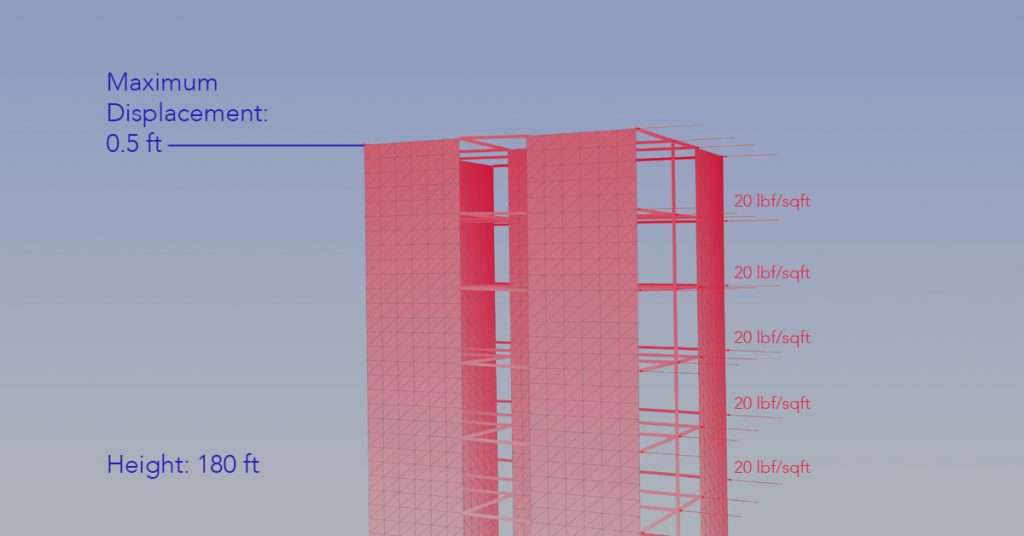

If one is able to produce a model in a short time and, thus, understand the structural behavior and environmental impact of the project, then they can teach themselves, especially if they can get real-time updates and feedback. For instance, technology allows one to move a column and understand when the span becomes too big by current standards or play with the size of windows to understand how much sunlight is getting into the room. Real-time rendering enables one to see what designed spaces look like from a human perspective as design decisions are made.

As highlighted earlier, learning architecture on real-life examples can be expensive and highly risky, but today there are more options for simulating, visualizing, and predicting behavior than ever before. These options offer great opportunities to experiment and reach the necessary amount of “design-decision” hours.

Combining Experience and Technology

However, this approach is not a replacement for a real experience. Rather, it is an enhancement that can make the real learning process faster. Having a good command of these design tools can put one in a better position in the design process.

I have experienced just this during my career. Being close to the position where the decisions are made compared to being close to the positions where the decisions are executed provides a very different perspective. Moreover, many of these tools can also bring experienced architects better control over their projects.

Creating innovative spaces that one has never designed before is always a challenge; technical support decreases risks and allows for potential issues to be discovered early in the process. Creating working teams that combine experience and “wisdom” with the new possibilities of our age often leads to remarkable results. By knowing what to check the design for and knowing how to check for it, surprises can be minimized and the final effect can be more predictable.

Conclusion

As discussed above, technology can really speed up the process of mastering architecture. Besides explaining benefits and strategies, another important trait is the possibility to advance field by field, thus not being overwhelmed by all the skills at once (skills required to be a great architect). Demonstrating even “partial mastery skills” helps to build trust and makes it easier to get more responsibilities and control within the projects. This approach could be observed as similar to the niche-based business strategies: getting as good as possible and winning even the smallest field, then expanding. If this strategy is widely recommended for conquering other disciplines, why would architecture be an exception?

Author Bio: Milan Dragoljevic is an architect focused on parametric design and the founder of the website/blog goparametric.com. His practice develops innovative designs through the use of algorithms. Current clients include different AEC industry subjects — from design studios to producers and general contractors. Besides providing parametric consultancy, he is a PhD candidate at Politecnico di Milano in Italy, where his research examines the use of data-driven design to improve design and construction processes.

Leave a Reply