The last fifteen years has been one wild ride for Fivecat Studio. We have survived two recessions, several natural disasters and a major terrorist attack within 40 miles of our front door. The confidence level of our clients has been riding the roller coaster of an uncertain, unpredictable economy. Project conversions have been up and down for more than a decade. Our best year, in terms of converting Prospects to Projects was 2004. The bottom was 2008. I know this as fact, because I track my firm’s Prospect to Project Ratio.

Today, I am sharing typically protected information; the data to determine the Prospect to Project Ratio for Fivecat Studio.

Don’t be deceived by the information I am presenting though. Revenues and profits are not shown in this data, and I can tell you, it looks very different than the trends shown here. In the spirit of Entrepreneur Architect’s mission to help you build a better business, I will share that private information another day.

Every year since Annmarie and I launched the firm in 1999, we’ve had a full workload. The size and scope of our projects have varied with the trends of the stock market, but we’ve always had work to do.

Below are two charts that present data collected throughout the history of our small firm architecture studio.

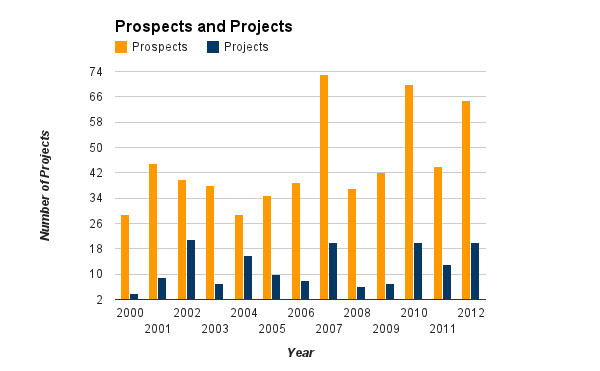

Prospects and Projects

This first chart shows the number of commissioned projects in reference to prospective clients. The orange bars represent the total number of proposals presented in the year indicated below. The year 2004 was the year that we finally gained some traction following the dip caused by the events of 9/11.

In 2006, I enrolled in the Academy of Entrepreneurial Excellence at Westchester Community College, where I fed my passion for business success, learned the basic rules of the game and applied new sales and marketing strategies at the firm. The tall orange bar from 2007 shows the result of that investment. That year we presented 73 proposals to prospective clients within a very focused target market.

The blue bars represent signed contracts and the Great Recession is clearly visible in the major drop seen in 2008 and 2009. Although the past few years appear to show improvement, what the graph does not reveal is the size and scope of the projects commissioned. As the economy creeps along, our high-end clients have reduced typical projects budgets from over $500,000 to less than $200,000. We’re busy, but projects are much smaller, resulting in less revenue.

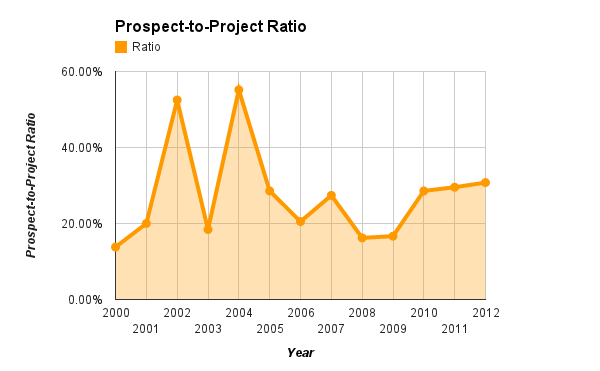

The Prospect to Project Ratio

This second graph shows our Prospect to Project Ratio, which is determined by dividing the number of signed contracts by the number of proposals presented. The “roller coaster” of client confidence is very clear in this image. Our best conversion years have been the pre-Great Recession years of 2002 and 2004. We can also see our slow climb out of the hole. Every year since 2008, we’ve gradually improved our conversion rate.

This past year has not been included in these charts because that data has not yet been fully collected. There is often a 6 to 12 month lag between presenting the proposal to a prospect and a new client returning a signed contract. The trend for 2013 continues to improve, so our fingers are crossed that conversions will continue to climb.

How To Use This Data

Collecting and organizing this data is great. It makes for really fancy and impressive looking graphs. Don’t you think?

Fancy graphs alone don’t really help your business or bottom line though.

Here is what I find most interesting about this data. Let’s go back to the first chart, Prospects and Projects. The orange bars labeled Prospects are the direct result of our marketing efforts. The blue bars, Projects, are the direct result of our sales system. Keeping the orange bars closer to the height of our blue bars will move the Prospect to Project Ratio line on the second chart up, indicating an improved conversion rate.

Preparing 73 proposals in 2007 looks very impressive on the chart, but my conversion rate was only 27% that year. If my conversion rate was closer to 50%, like it was in 2004, I would have only needed to prepare 40 proposals. That would have been 33 interviews, 33 proposals and 33 follow-ups that would not have required my attention. That was time that I could have used to improve my sales system (or to design better architecture).

We ultimately want to know how many sales are required per year to be profitable. Then we want to build an efficient and effective sales system that yields the highest conversion rate possible, bringing the orange bars down, closer to the level of the blue bars.

In time, we established a specific conversion rate. Today we know, and plan for, the specific number of interviews and proposals we need to submit for a profitable year.

The ideas presented here are simplified. There are many other factors, like project scope, revenues and profit margin that also play a part in the equation. For today, though, I wanted to keep it simple and show you how the relationship between Prospects and Projects lead to a specific conversion rate. I hope you can take this information and start to develop your own charts. The things you will learn from this data will be transformative.

Do you know your Prospect to Project Ratio? Tracking such data will help you see where you’ve been, confirm that your current strategies are working and will let you predict the trends of your future. How are your conversions? Are you experiencing similar trends? Please share your thoughts in the comments below.

***

Our sales system at Fivecat Studio includes our proprietary Hybrid Proposal for Architectural Services. Click here to learn more.

Hi Mark,

Thanks again for another great post. I always do a conversion chart and the thing I am often struck by is how many of those are “repeat” clients. They are the backbone of our practice, year after year.

One of the issues I always have with my conversion charting is trying to differentiate the size of the job that is being converted. Example, one new house equals 4 small renovations. Four renovations use up far more of my time and my staff dealing with additional clients,more contractors, more approvals process, more construction job site visits to make. On the flip side, sometimes the smaller projects work out great as while others are awaiting approvals or bidding, we have productive design to accomplish on small projects. It is definitely about balance…and about trying to run the business instead of the business running me. Not as simple as that sounds!

On another note, hope the virtual office concept is working out. We’ve been experimenting with that recently by necessity, having been hit by a fuel spill at our office…We finally have Health Dept blessing to be back in our space. Virtual was fabulous to accomplish a lot of our work, however found that not having the team on hand together daily is really tough! best, Carol

Carol, there is so much more we can add to these data. The idea of developing a formula for large projects vs small projects, maybe also high profit projects to break even or loss. That would be very interesting to see that all on one graph.

The virtual office is working out great. I do miss the spontaneity of the open office full of staff, but we do get lots of work done. We have a weekly face-to-face meeting and stay in touch via telephone and email. I will write an article about it. Watch for it in the next few months.

Great article, Mark. We’ve shared it around the office this morning. One of my intentions this year is to be much more focused on these sorts of things.

That’s terrific. I’m glad it’s helpful. Thanks for the feedback.

Great Article Mark. I have just started collecting this data and tracking my conversion rate. I appreciated seeing your charts over several years and reading your analysis of what it all meant. Thanks!

I am glad you are finding this post useful.

Mark:

I don’t understand.

Did you say your typical project budgets are “reduced… $500,000 to $200,000” ?

Is that construction budget or design budget?

If that is design budget sounds too good to be true,obviously.

If that is construction budget, that doesn’t sound very high at all. Barely enough to justify hiring an architect. $200,000 could not build a single family house here, let alone be enough to pay even a cheap draftsman. $500,000 would barely inspire anyone to do a custom design, it would probably be a planbook redraw here. I get mad when they just do planbook for the $1m plus stuff.

Please explain.

Michael:

Those are construction budgets referring to residential additions and alterations projects.

As an architectural photographer, I track my prospect/conversion numbers as well and also struggle with the trade-off between more, lower-value projects vs. fewer, high-value ones. One school of thought says that any work, at any budget, is good work. Another school cautions that if you completely fill your schedule with low budget work, you’ll be the victim of your own success when you can’t make room to accommodate the higher-budget projects that do come along and you find that can’t hit your numbers for the year if you’re only getting low-budget work. So a bunch of years ago, I tried to start accounting for this while still acknowledging the important role that smaller projects can play in the budgetary mix, by dividing target projects in to three budget categories, low, medium, and high, and setting separate targets for each. I can track and graph separate conversion rates for each level and know where to try to target my marketing year-over-year. It also gives me a plan, and therefore the confidence, to turn down low-budget work (or at least consider doing so!) once I’ve hit that number for the year. I don’t have to chase little projects all year long if I know that I’ve gotten plenty of those and so my time is better spent marketing to potentially higher-paying prospects, following up with old clients at that level, or other things to generate work in the medium and highest-paying ranges.

Lastly, while we all obviously need cash flow to pay our bills and feed our families, it is important to remember that not everything of value is financial. I will sometimes accept extra “low-paying” jobs beyond my targets, or “extra-low-paying” jobs that might not even meet my usual minimum fee, because of the networking possibilities, the exposure, or frankly because it’s just a really damn cool project that I want to shoot. However, when doing so I always have to remind myself that the ultimate goal of networking and exposure is to be paid for what we love to do. Simply doing what we love might keep us happy, but it won’t keep us fed. As I tell students who ask about shooting work for magazines as a way of gaining exposure, “we should never be so desperate, or so vain, that we forget that the ultimate goal of getting published is to get paid.”

The job size is a nice indicator, I agree, as it reflects the clients’ expenditure trends as well as the trustworthiness of the architect along the time-frame. My question is: has the clients’ selection criteria to an architect changed along this time-frame? My best. Oday

This does not consider enough variables such as pricepoint, profit, volume, and break even.

So the question is, how much are you getting in fees for this type of work?

Projects that are in the $200k- 500k construction budgets are often price sensitive and in my market often go to the unlicensed designers . So if I charge maybe 2 1/2% I can compete if they are charging 1%. After that my conversation rate would go down expotentially. But if I try and compete at 1% my conversion rate would go up but I wouldn’t make any money because I take the time to do quality work (which they usually do not).

Then the $1m and up are different animals. People expect to pay more but are also fusier and take longer to close the deal.

Also, if a $200k client calls I make no bones about my fees and tell them right up front that if they want to shop it I’ll pass even showing up to meet. This is the price and wil you have a check ready upon my arrival. And they know it is harder to get an architect to show up on a small job . So my conversation rate is high on that one because I’m not showing up unless they sound serious but they will seldom call an architect in the first place.

The $1m budget job is going to get more schmoozing and I will expect that they will have 3 architects bidding on the job. So my conversion rates on those jobs are about 33%.

If they were 10% I would know to get a new brand of mouthwash. But it is almost more statistics than charm.

So each type of job will have it;s own characteristics. My conversion rate on planned cities is 0%. My batting average there is 1 strike 0 hits in 35 years. But I don’t put much stock in that kind of venture.

Michael

I agree with you that there is much more that goes into conversion rates. I acknowledge that in the article. As always, I appreciate your thoughts.

Our fee is based on 12% of construction cost. A $250,000 project yields a gross fee of $30,000.

I am blown away that you can get these fees.

In my market most clients would just go to the unlicensed designers for a fraction

of that.

Are unlicensed designers allowed in your market?

In New York, there are few significant projects that can be done without a license. With that said though, there are plenty of architects and contractors with “friends” that provide services for much less than our fee.

Our fee is intentionally higher than most in the region for 3 reasons; 1. A high fee immediately filters out the “bottom feeders” looking for the lowest price. There is a market there, but it’s not the market in which we choose to work. 2. We are a full service, high touch firm. We spend a tremendous number of hours in design and managing the experience of a major construction project. Our goal is a happy client and that takes time and attention. The fee we are paid is commensurate with the value we provide. 3. Our fee is set so that we can pay our expenses and end each project with a profit. It’s not high just to be high. It’s high because that is what we need to be a healthy profitable business.

In my experience, most architects are not charging enough. They are afraid to push their fees beyond what they think a client would pay. My advice is to provide massive value so that you can use your happy clients as references and slowly move your fees up until you hit the true market ceiling for what you are providing.

Thanks for your candor and rationale…

Our batting percentage hovers in the 33% range. I am often surprised by projects we get and dismayed at some I thought were expected, and do not get. The best feedback I get is from customers who will speak to me about the “why” we were not selected….and it varies wildly… from missing punctuation in a proposal, to fees, to freebies they understood should be included in the proposal, and I try to heed their input for the next prospect.

Occasionally, we’ll see a competitors proposal with the firm’s name deleted, and see some of the needed tasks that are omitted…making it very difficult for a customer to compare “apples to apples”, and fueling a relationship that can only grow adversarial as “extra services” invoices are issued.

Steve: I think that undercutting by other firms is a big part of our problem with perceived value of architects from the public’s POV.

I worked in a firm where the conversion rate was tracked based upon hours and therefore dollars spent preparing proposals against dollars won in fees. This then starts to take into account different sizes and fee basis – although not actual profit.